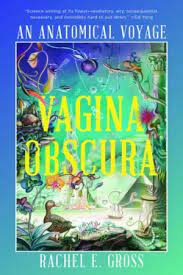

Vagina Obscura: An Anatomical Voyage

Vagina Obscura: An Anatomical Voyage, by Rachel E. Gross (2022) is a remarkable combination of information about anatomy, health, history, science, biography, and sociology related to the female organs. It is also my choice for the topic of Health for the Nonfiction Reader Challenge.

The

book organizes these organs into separate chapters according to their

presenting characteristic:

- Desire (Glans Clitoris)

- Wholeness (Internal Clitoris)

- Resilience (Vagina)

- Protection (Vaginal Microbiome)

- Creation (Egg Cell)

- Power (Ovaries)

- Regeneration (Uterus)

- Beauty (Neovagina)

Each

chapter focuses on the particular body part using the stories of medical

personnel, specific women, and historical figures to give background and information

about the organ’s function, development and physical description. Although the

narrative often includes detailed biological and technical data, Gross makes it

as interesting as a novel. I found myself unable to put the book down at times,

wanting to know more about the continuing “story.”

A

recurring theme throughout the book is how little is known about these organs,

because medicine and science have never focused on them. Male doctors and psychiatrists

have written about the vagina, uterus and ovaries throughout history without

actually studying them. And clinical trials have used only male bodies to

determine basic information about the function and health of the human body.

This reminded me of the chapter on health in the book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (see my post of April 4, 2022). Gross

writes that it wasn’t until 1991 that the U.S. required women and minorities to

be included in clinical trials. And it was as recently as 2014 (!!!) that the

National Institutes of Health started studying women’s bodies (e.g., vaginas,

vulvas, uteruses, ovaries). And the research that has been done on women’s

bodies has focused only on their function in child-bearing.

Not only have women’s bodies been ignored by

science, but also women involved in scientific projects as well. One of the examples

Gross writes about is Miriam Menkin. I had never heard of her, but she was the

first person to fertilize a human egg in the laboratory (outside the body).

This enabled the development of IVF treatments as well as the understanding of how

the egg and embryo develop, but she is not mentioned in most information about

these areas (the men she worked with are, however).

I was surprised by how much I didn’t know about my

own female body. Textbooks tell us that a female is born with all the eggs she

will have in her life, but recent research has proven that isn’t true. It turns

out that ovaries have stem cells that allow the ovaries to make new eggs until

menopause. This research was disbelieved at first by many in the medical field.

But Gross, referring to Jon Tilly, the reproductive scientist who discovered

this, writes “He compares the idea of ovaries making new eggs to the idea that

the brain generates new neurons—a finding the field of neuroscience considered

ludicrous before the 1990s but is now accepted as scientific fact.”

I also had never known that the clitoris is not

just an external organ, but has a large internal section as well. Gross reports

the information she learned from Dr. Helen O’Connell, an Australian urologist

who has studied the clitoris (one of the few people to ever do so) and whose

doctoral thesis is “perhaps the most thorough exploration of the anatomy and

history of the human clitoris ever written”.

O’Connell became interested in this organ during

her medical studies, when she realized how much information was devoted to

studying the penis, while almost nothing was written about the clitoris. In

referring to her medical textbooks, she said, “The clitoris barely got a cameo;

a cross-section of the female pelvis omitted it entirely. Meanwhile, four pages

were devoted to the penis.”

The Afterword consists

of information from conversations and emails Gross had with Bo Laurent, “the

most well-known intersex activist in the world.” Gross reports that Laurent

encouraged her to “investigate another consequence of our anatomical ignorance

about this part of the body: a form of genital cutting still being practiced

right here in the United States, on children born with ‘unusual sex anatomy.’”

Gross has interviewed many people in the medical

field, as well as women who have been ignored, disbelieved, and misdiagnosed when

their medical problem was related to their genital organs. She was given “unparalleled

access to labs and the latest research.” And she has put it all together in an

extremely interesting, readable, amazing narrative.

At the beginning of the book, she tells the reader:

“This

book was written for any woman—any person—who has found themselves mystified by

their own body. Anyone who has felt the nagging suspicion that what they have

read about their anatomy wasn’t written for them, or by someone like them. You were

right. This book was written for you. It was written for anyone who has felt

unable to talk about their body in language that others could understand. Anyone

who wants to better understand the legacy they were born with, by virtue of

their reproductive organs and the chromosomes dancing within their every cell.”

This book has certainly helped me better understand

the legacy I was born with and has enabled me to realize just how magnificent the

female body is.

Comments

Post a Comment